The agreement is essential but harsh conditions may hurt domestic market, especially agriculture and allied farm sector

THE UPENDING of 12 Nation Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) (Free Trade) Agreement, by US President Donald Trump in the first week of his office early this year has precipitated an evidential geo-political shift in trade to the Asia Pacific region.

A signature legacy deal of Obama Administration, TPP was envisaged to deftly manoeuvre “emerging” priorities for US.

Among top key, to contain global aspirations and regional economic assertiveness of China, to strengthen a composite “multilateral trade and investment construct” in veritably fastest growing economies constituting 40 per cent of the global GDP, and, to shift its multi-decade old anchor of strategic governance and security theatre “pivot” from Middle East to Asia”, reassuring close allies of its presence in the region.

New Delhi recognises this “economic, geo-political and security architecture” shift as was brought out explicitly by External Affairs Minister, Sushma Swaraj in the recently concluded 9th edition of the Delhi Dialogue Series, an annual Track 1.5 event.

India hence on its part is speeding up efforts by hinging on Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a proposed free trade agreement (FTA) between Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) members and the five states with which ASEAN has existing FTAs.

These include Australia, China, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand. Further, to enhance these ties beyond economic integration to areas of strategic and maritime cooperation, India has extended an invite to all the heads of ASEAN member countries for Republic Day celebrations next year.

The RCEP is yet under negotiations but is expected to be concluded this year. India presently is hosting the 19th round at Hyderabad from July 17-28, 2017.

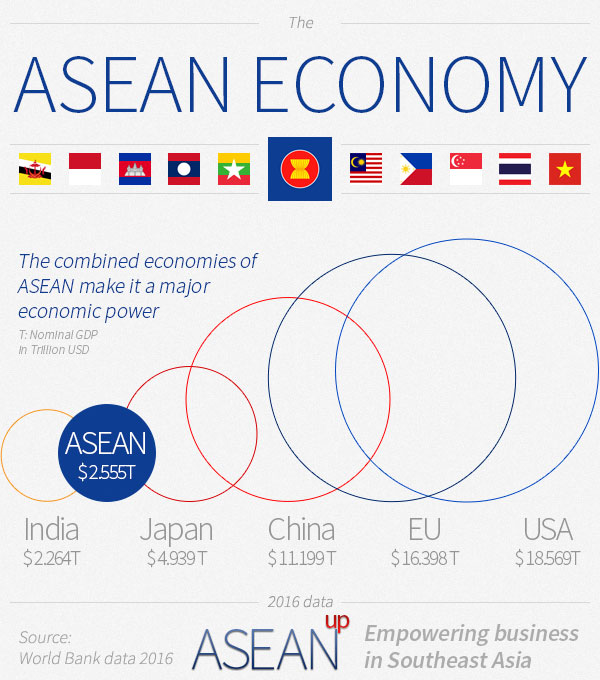

With a combined population of 1.8 billion people and GDP of over US$ 2.8 trillion, its attractive size is widely believed as an alternative to Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) and shall establish an ASEAN-India Regional Trade & Investment Area (RTIA).

India has a huge trade deficit with ASEAN countries. Add cumulative trade deficit of ASEAN+5, including China (US$ 53 billion), and we have a grim scenario.

Despite the impressive prospects, however, the gains and outcomes for India may not be as significant as assumed.

For one, India has a huge trade deficit with ASEAN countries. Whilst India’s exports to ASEAN increased from US$ 10.41 billion (2005-06) to US$ 25.20 billion (2015-16), imports over the same period quadrupled from US$ 10.81 bilion to US$ 39.84 billion, as per an ASSOCHAM report.

Despite registering a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 9.2 per cent, imports from ASEAN were up from 7.3 per cent of the total import in 2005-06 to 10.5 per cent in 2015-16. Over the same period, share of exports to ASEAN in India’s total exports fell from 10.1 per cent to 9.6 per cent witnessing a gradual decline.

The net trade deficit at US$ 14 billion appears less, however should be a cause of concern considering that this is just a quantum of imbalance with prominent countries of Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia with whom India signed comprehensive commercial agreements (CECA) and the relationships were upgraded to “strategic partnerships” by 2012.

These constitute the major trade deficit countries. Just over 6~7 major categories contribute roughly around 50 per cent of the import trade, whereas on export front, India is yet to see the reciprocity of member nations to allow increase in our “offensive areas of trade” in Services (55 per cent of India’s GDP) which includes IT & IT-enabled services, resources and software exports and solutions.

Add cumulative trade deficit of ASEAN+5, including of China (US$ 53 billion deficit), and we see a grimmer reflection of where we stand on our trade partnerships with the region.

India's export duties are much higher (40% and above) than those in ASEAN countries (10-15%)

The RCEP principally shall subsume bilateral individual relationships to an “Umbrella Multilateral body of Agreement” on trade in merchandise products, investments and, most importantly, services. The removal of “tariff” and “non-tariff” barriers quintessentially means “zero duties” across a vast range of products and services making India an attractive market for cheap imports sans any protection measures.

With New Delhi already agreeing 'in principle' to a “three-tier tariff” reduction across product, industrial and agriculture baskets, these concessions might not translate as advantageous for India when similar tariff cuts come into force through RCEP within trading nations.

Agriculture and allied sector, a “defensive areas of interest” for India, shall take the hardest hit through duty free imports of subsidised products under FTA. Even a cursory look at Indian tariff alignments for Agri commodity exports shows that the tariff rates are much higher (upwards of 40 per cent) as compared to ASEAN (10~15 per cent).

This is sufficient ground to further rile the already “stressed agri and crisis ridden farm sector” by cheap commodity imports. Australia, one of the ASEAN+6 countries, is already seeking to move into the small scale dairy sector, a part of India’s informal economy supporting livelihood of millions of farmers and a hitherto protected sector from global trade gyrations.

Further, India’s track record has been less than exemplary in negotiating trade and tariff’s deal even at WTO, as seen last year in the Nairobi round. India had to bury its assiduously built up gains from Doha Agenda Framework (2001) succumbing to developed economy bloc on matters of “our food security” and “their subsidised farm exports”.

India returned from Nairobi with only a “work program” under bilateral negotiations in a perpetual “draft stage” on (SSM) “Special Safeguards Mechanisms” and is presently sweating it out in trade negotiations to protect its interest at Geneva.

India’s track record has been less than exemplary in negotiating trade and tariff’s deal even at WTO, as seen last year in the Nairobi round

The equation hence pans out as WTO+ (“Plus”- introduction of “Singapore Issues” from Cancun Ministerial Conference (2003) adopted at Nairobi on Market Access and Interlinked E-Commerce) and ASEAN free trade conditions on Intellectual Property Rights, Dispute Settlement and Tariff reduced “market access” under RCEP. All this makes it far more stringent, allowing no or restricted manoeuvring room for India to negotiate any gains in the immediate term, once RCEP negotiations are concluded.

With India undertaking several steps towards “market-linked reforms”, the resilience of the economy is clearly under strain. All sectors are witnessing de-growth over the corresponding comparable period. India’s large jobs sectors are still struggling to take off and voices demanding “to go protectionist” for certain critical sectors of the economy are getting shriller by the day. The last thing India needs is an overarching “Free Trade Agreement”adding to the distressed “reform” narrative and hanging by a mere thread over the precipice.

New Delhi must know, a tide can only lift so many boats at a time, rest do run aground.

(Abhishek Joshi is a New Delhi-based Policy Analyst)